PRECIOUS METALS

Gold

We only ever use precious metals such as gold, silver, platinum and palladium (also a platinum metal) to produce our pieces of jewellery.

Fine (pure) gold is too soft to be processed into jewellery. For this reason, it is usually alloyed (mixed) with silver, copper or platinum metals. When doing this, the fine gold content of the alloy must not fall below certain statutory levels. In Austria, the alloys are 14k gold (in which 585 out of every 1,000 parts are fine gold) and 18k gold (750 out of every 1,000 parts fine gold)

Accordingly, hallmarking a piece of jewellery made of gold with the figure “750” or “585” signifies the fine gold content is the equivalent of either 750 out of every 1,000 parts (18k), or 585 out of every 1,000 (14k) respectively.

Essentially, the rule is this: the higher the fine gold content, the more valuable the material.

Platinum

In its own right, platinum is white with a greyish tint. Although it is more difficult to process than white gold, it boasts a reputation for being higher-quality. It has a higher specific weight than gold. As a result, jewellery made from platinum is heavier than that using white gold. Platinum alloying is also used to produce jewellery. Out of every 1,000 parts, 900 are fine platinum, and 100 parts additional metals. The fine content hallmark for platinum, therefore, is “900”.

Silver

Like fine gold, fine silver in its pure form is simply too soft for designing jewellery.

As a result, it is almost always mixed with copper. The main silver to be used is sterling silver, a silver alloy consisting of 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper. The fine content hallmark in this case will be “925”.

In the case of silver tableware, meanwhile, “835” silver is usually used.

Silver reacts to sulphur compounds in the air, forming a black-grey coating on the surface, a process also known as “oxidising”.

To prevent or delay this so-called “tarnishing”, jewellery made from silver is often rhodium-plated. Rhodium plating is the name given to the process of electroplating the jewellery with rhodium, a platinum metal.

PRECIOUS STONES

Diamond

Diamonds have been surrounded by countless myths and sagas for millennia, and are widely acknowledged as the most valuable of all precious stones. The aura of elementary interaction of the Earth’s forces associated with the stone’s natural formation process provide the foundation for its natural rarity and inherent exclusivity. While it can safely be presumed that man-made manufacturing methods could topple a ruler’s throne, the claim to authenticity that comes with ownership of a diamond remains literally and metaphorically unbreakable.

Named “Adamans” – the impregnable one – by the Greeks, a series of etymological detours over the centuries have eventually led to it being known as the diamond in modern times. Along with its unsurpassed hardness – it is 140 times harder to cut than the ruby or sapphire – the diamond differs in several ways from all other stones. Above all, there is the fact that it exists thanks to just one element, namely carbon. Then – and more appealingly to the beholder – there is its unique capacity to sparkle, the breathtaking result of the cut!

“I could have taken it for a fragment of broken glass and thrown it away,” said Edward VII when given the Cullinan, the world’s largest uncut diamond, as a gift.

Our ability to cut diamonds, first recognised in the mid-15th century, was destined to raise the stone to the heavens. If we look at a cut diamond with a magnifying glass for a little too long, however, then its hard lustre can begin to bring tears to our eyes. Humans have been captivated by its extraordinary light refraction, and the related “fire”, or gemstone dispersion, since time immemorial.

It is not just diamonds’ specific lustre that makes them so impressive, however, or their size. In certain cases, it is also their colour that makes them so unique and sought-after. Over time Indian Moguls, Louis XIV, Russian Tsars and English monarchs were all mesmerised by the stone. One might think for a moment of the Dresden Green Diamond acquired by Augustus the Strong, the blue Hope Diamond, or the Hapsburgs’ yellow Florentine Diamond. The fascination with these rare and valuable varieties remains unbroken: some of these stones, known nowadays as “fancy diamonds”, have achieved fairytale prices at auction in recent years.

Russia, South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Congo, Sierra Leone, Australia, Canada and Brazil

10

Leo

The Ancient Greeks believed the diamond could render toxins ineffective, free the spirit from anxieties, and make its owner invincible.

Some diamond pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

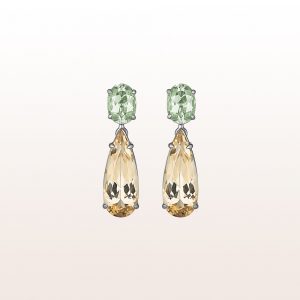

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistStud earrings diamond, iolite, sapphire, tanzanite

1.475$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Ruby

The ruby has been the most mysterious precious stone since time immemorial, and has lost none of its fascination over the centuries. People believed steadfastly in their supernatural powers in ancient times. Later on, the rich and famous, from Maharajahs to Maria Antoinette and Hollywood divas, all became addicted to them, prizing above all the flattering way they would sparkle on the skin in candlelight. This also gave them the reputation of being a “stone of the evening”.

Together with its brother the sapphire, the ruby is one of the best-known and most elegant members of the exceedingly colourful corundum family of stones. Due to its rarity, the ruby has been considered an extremely valuable precious stone for centuries now. Sometimes it is even more expensive than the diamond: Cellini, famous goldsmith of the Renaissance, reported that people were paying up to eight times more for rubies than they were for diamonds at the time. Today, too, carat prices for top qualities have been rising continuously and steeply for years now, as large stones of outstanding quality are actually rarer than comparable diamonds.

The “pigeon blood” classification for deep, rich red stones with a light undertone of blue is without a shadow of a doubt the most valuable shade in the colour spectrum for rubies, which ranges from delicate pink tones through to dark purple. Rubies from Burma (Myanmar) are particularly popular with connoisseurs and lovers of this stone, enjoying the highest level of provenance and strongest demand.

Burma, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Madagascar

Corundum

Aries

The ruby is viewed as the stone of life, passion and love, and said to bestow dignity, recognition and power upon its owner. It is credited with bringing its wearer determination and confidence in a revitalising and strengthening way.

Some ruby pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

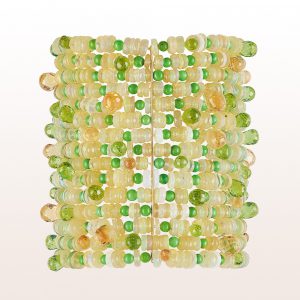

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet, labradorite, topaz and rubies

2.792$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Sapphire

The Ancient Persians were once convinced that the blue of the sky was simply one vast sapphire, on which the Earth stood. It may be that the roots of its reputation as the “stone of the day” also lie in this colourful coincidence. There’s little doubt, however – in contrast to the ruby – that the sapphire unfolds its most beautiful luminescent properties best in the daylight. Like the ruby – a close relation, mineralogically speaking – sapphires belong to the corundum family.

When we think of sapphires, we immediately tend to think of something deep-blue in colour, unfolding with a mysterious twinkle. The colour spectrum of the classic blue sapphire ranges from light blue to ink-blue, with a glowing cornflower blue considered the most highly-prized colour of all. The loveliest and best sapphires originate from Kashmir.

As well as the classic blue, sapphires can be found in a wide range of other bright colours, from yellow or pink through to violet and green. One highly valuable colour variant bears the poetic name Padparadscha, or “Dawn”. This special, orange-coloured sapphire offers unique blends of salmon-pink tones, and can fetch incredible prices internationally.

Even if clarity is a significant criterion in quality, of course, it is important to remember that not all kinds of inclusion are equally flawed. For example, deposits of fine rutile crystal can allow for what is known as “asterism”, when the stone features a six-pointed light star – and becomes a “star sapphire”, a precious stone with particular rarity value. As well as this, the visual appearance of inclusions can be used to prove where a stone was mined, and whether it has been heat-treated to improve the colour or is a (more valuable) untreated stone.

Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand and Kashmir

Corundum

September

Taurus, Virgo, Libra, Pisces

Prized by mysticists as the stone said to keep our understanding clear and the heart free from cravings, protect us from unwelcome, intrusive love, and preserve the loyalty of true love. Thanks to this supposed capacity to raise human spirits, for example, the sapphire has been worn in Bishop’s rings since the 14th century, and has long been very popular for use as a stone in engagement rings thanks to its symbolism of pure, chaste love.

Some sapphire pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Emerald

There was just one source of emeralds to speak of in antiquity, buried deep in the deserts of southern Egypt. Despite this, the stones could be found throughout the ancient world, from markets in Babylonia to medicine cupboards in China and the observatories of Vedic astrologers. The emerald mines of Cleopatra, which were steeped in legend and continued to operate for 1,000 years, were thought to have been lost for five centuries, until they were rediscovered by the French mineralogist and explorer Frédéric Cailliaud in 1817. The exquisite stones weren’t just prized in Egypt, however, but also in Ancient Rome. Emperor Nero is said to have held emeralds in front of his eyes in an effort to protect himself from the dazzling sunlight in the Arena – sunglasses made from emeralds, you might say! Nero always had his eccentric side, of course.

Centuries later, when Spanish Conquistadores seized magnificent emerald jewellery from Inca and Aztec temples, it was not long before the sources of the stones in Colombia – where the best emeralds are found to this day – became accessible for Europe too.

The emerald is considered the most precious stone of the group of beryls, and along with the sapphire and ruby, is one of the three most valuable coloured stones. This is also shown in the fact that in numerous countries around the world, state and crown jewels are home to magnificent examples of this variety of stone. The Vienna Treasure Chamber, for example, contains an ointment jar 12 cm in size and weighing over 2,200 carats – which was cut from a single crystal.

It’s extremely rare to find totally clear emeralds, but if one does turn up with such top qualities, you can be pretty sure it’s a real rarity. This is because most stones have what is referred to as a “jardin”, a garden of more or less pronounced inclusions. These will often lend the stone a certain liveliness, and allow experts to conclude the stone’s country of origin and even the mine it came from.

Colombia, Afghanistan, Brazil, Madagascar, Pakistan, Namibia, Mozambique and Zambia

7,5-8

The emerald is considered the stone of truth, intuition and prophesying. From East to West, ancient cultures around the world would grind emeralds into powder to cure a variety of ailments ranging from poisonings to epilepsy, to scare off snakes and dragons, restore eyesight (as championed by Nero) and stimulate fertility. To this day, the Chinese crush emeralds of lower quality to be used for therapeutic purposes.

Some emerald pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

PRECIOUS STONES

Agate

Agate has long been associated with human history, and together with jasper, was being used to produce hunting weapons and tools thousands of years ago. It was later discovered as a jewellery stone – in opulent signet ring engravings and gems, for example – and eventually also used to make artistic drinking vessels and works of art. Its variable, frequently striped, appearance can be traced back to the deposition of a range of minerals such as iron, manganese and chrome, as a result of which agate features exceptionally rich colouring. It has also been customary to colour agate using brines since time immemorial.

Germany, Brazil, Uruguay, Australia, China, Caucasus region and Mexico

6,5-7

Taurus, Capricorn

Agate is said to protect the wearer against evil and to strengthen one’s willpower. It was already being used as a lucky charm at the time of the Ancient Egyptians and Greeks. The stone is also said to have positive effects against sleeping disorders, as it reduces inner tension.

Some agate pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet, rose quartz, zircon and bluesea agate

1.601$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Andalusite

yellow-olive green, brownish-red

Spain, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Russia, Sri Lanka and USA

7,5 – 8

Amethyst

This unusual stone is exotic not just in name but also in nature. It has a summery blue through to turquoise-green appearance, lending it a fresh, youthful feel. Contrary to initial assumption, however, its name does not refer to its excavation site being in the Amazon; rather, it is associated with Alexander von Humboldt’s voyages of discovery in general. On one of his expeditions, the Prussian naturalist and explorer encountered indigenous women, living independently, who were wearing amulets featuring the unusual stone.

According to his own reports, the women, designated by him as “Amazons”, made such a deep impression on him that they were responsible for the naming of this stone.

Brazil, Madagascar, Zambia and Uruguay

7

February

The Greeks wore the amethyst not just to combat drunkenness, but also witchcraft and evil thoughts. It was said to have the power to protect against false friends, avert dangers and reverse bad thoughts.

Some amethyst pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

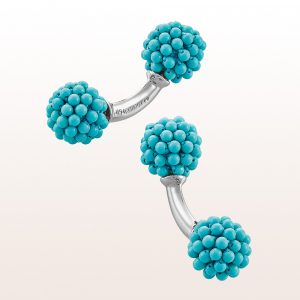

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlistCufflinks crystal quartz, mother of pearls

5.058$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Amazonite

This unusual stone is exotic not just in name but also in nature. It has a summery blue through to turquoise-green appearance, lending it a fresh, youthful feel. Contrary to initial assumption, however, its name does not refer to its excavation site being in the Amazon; rather, it is associated with Alexander von Humboldt’s voyages of discovery in general. On one of his expeditions, the Prussian naturalist and explorer encountered indigenous women, living independently, who were wearing amulets featuring the unusual stone.

According to his own reports, the women, designated by him as “Amazons”, made such a deep impression on him that they were responsible for the naming of this stone.

Sweden, Poland, Russia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Myanmar, Brazil, Canada and USA

Feldspar

6-6,5

Aquarius, Cancer

Amazonite is said to have a counterpoise effect, lend the wearer joie de vivre, and to help against headaches. The ancient Egyptians are also said to have viewed it as a sacred stone, which would have been worn as an amulet to ward off disease and snakebites.

Some amazonite pieces

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet apatite, rock crystal, amazonite, calcite

115$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Apatite

turquoish-blue to green

Brazil, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Mexico, Myanmar, South Africa and USA

Apatite

5

March

Sagittarius

This stone is said to counteract apathy and lethargy by imbuing the wearer with renewed motivation, optimism and determination, thereby strengthening self-confidence.

Some apatite pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet apatite, rock crystal, amazonite, calcite

115$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

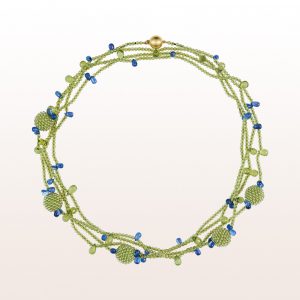

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace turquoise, apatite, peridot, zircon

1.738$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace apatite, peridot, turquoise, zircon

1.865$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace apatite, peridot, lemon citrine

2.529$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Aquamarine

Legend has it that while playing with mermaids, sea horses carried off the aquamarine – the mermaids’ treasure – and took it off towards the light. Unsurprisingly, then, this stone takes both its colour and its name from the seawater (“aqua” being Latin for water, and “mare” for the sea). In mineral terms, it belongs to the group of beryls, which also includes the emerald. Far less flawed than this most precious of its related stones, the seawater-coloured beryl differs from the emerald by its considerably lower rarity value.

Dark aquamarines, which often reach the limit of sapphire blue, are far rarer and more sought-after than light stones, and significantly more valuable as a result. The most famous precious stones of this type come from the Santa Maria mine in Brazil.

Brazil, Afghanistan, Madagascar and Urals region

7,5-8

March

Aquamarine is considered the stone of serenity, lightness and pleasure, and to have the power to help us achieve harmony and well-being. As a result, it also is supposed to combat feelings of depression, increase self-confidence, and bestow far-sightedness, prudence and stamina upon its wearer. In partnerships, it is viewed as helpful in deepening love and loyalty.

Some aquamarine pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Beryl

The Ancient Greeks were convinced that beryl could improve their status and preserve love within marriage. They also realised that this precious stone was capable of refracting and deflecting light. Based on this capacity, convexly polished beryls were used to produce “reading stones” – the origin of the German word for reading glasses or spectacles, Brille.

The group of precious beryls includes all those colour varieties of the beryl group that are not green or light-blue, since despite being related mineralogically, these are classified separately as emeralds or aquamarines. Examples of stones that fall into the group of precious beryls include gold beryl, as does the light-pink morganite, which was named after the American financier and collector J. P. Morgan.

Afghanistan, Brazil, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe

7,5-8

May

Taurus

Jews revered beryl as a magical stone said to consolidate one’s faith in God, and the Revelation of John, last book of the Bible, describes the stone as the eighth of the twelve foundation stones to be used in Jerusalem’s city wall. Benedictine abbess and Christian mystic Hildegard of Bingen also dedicated herself to the effects of beryl. It is said to help combat a variety of ailments, including travel fever and poor eyesight.

Some beryl pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Calcite

colourless to gold-yellow

USA, Brazil, Mexico and many other sites

Calcite

3

Also known as calcspar, calcite is said to have a healing effect on bones, from which its traditional German-language name, Beinbruchstein – “fracture stone” – derives. As well as this, it is said to have a positive effect on intellectual capacity, and help with memory and creativity.

Some calcite pieces

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet apatite, rock crystal, amazonite, calcite

115$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Carnelian

Carnelian was already being used in the ancient world to produce precious small works of art and magnificent gems. Although the stone continues to enjoy great popularity to this day, much of the carnelian produced nowadays is actually coloured and heat-treated agate. Natural carnelian shows a cloudy colour distribution in transmitted light, while coloured agate has a streaky tint.

One interesting cultural and historical example of the stone’s traditional use in signet rings is in the Luther rose, a seal cut in carnelian with Martin Luther’s crest, now on public display at the Green Vault in Dresden.

Brazil, India, Uruguay, Australia, Germany, Poland and Slovakia

6,5-7

September

Aries, Gemini, Virgo

Due to its blood-red colouring, the Ancient Egyptians viewed carnelian as the stone of life; it is mentioned in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and played an important role in the burial rituals of the time. Hildegard von Bingen described the stone as also having a positive effect on the immune system, and it is said to this day to provide vitality.

Some carnelian pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings carnelian, rhodochrosite, topaz

3.730$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Chalcedony

Although the name of this stone dates back to the ancient city of Chalchedon in Bithynia (modern Turkey), it has proven impossible to establish a more precise connection. Pliny the Elder, and later Albertus Magnus, use the designation, defining it in connection with minerals. Several of the so-called “microcrystalline quartzes” are classified under the designation today; as well as chalcedony itself, these include agate, chrysoprase, heliotrope, jasper, carnelian and onyx.

Brazil, India, Madagascar, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka and Uruguay

Group of microcrystalline quartzes

6,5-7

June

Blue chalcedony is said to bring inner peace and increase attentiveness, as well as strengthening rhetoric, creating self-confidence, and resolving inhibitions and anxiety in the wearer by increasing assertiveness.

Some chalcedony pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace chalcedony, amethyst, pearls

3.888$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings chalcedony, sapphire, aquamarine

3.825$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Chrysoprase

Back in the Middle Ages, chrysoprase was one of the most sought-after precious stones of its time, and to this day it is viewed as the most valuable variety of the chalcedony group, part of the quartzes. The high esteem in which chrysoprase has been held historically is demonstrated by its use in opulent decorative works to be found at St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, Karlstein Castle – and later also Sanssouci Palace, at the behest of Frederick the Great, who deemed it his favourite stone. The stone’s luscious green colour, which also gives it its name, and its freshness mean it has remained hugely popular in jewellery down the ages.

Poland, Australia, Brazil, India, Kazakhstan, Russia and South Africa

6,5-7

May

Cancer, Virgo

In Ancient Egypt, chrysoprase was said to offer protection against dark forces and plagues. The Ancient Greeks believed it countered depression, and Hildegard von Bingen credited it with having an effect against epilepsy and poison.

Some chrysoprase pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings coral, turquoise, chrysoprase

1.043$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Citrine

Although its lemon-yellow tones mean this stone was destined to be named after the fruit, its chromophoric substance (responsible for its colouring) is actually iron. The nuance of colours varies depending on where the stone originates, and on differing soil composition from place to place. Although naturally a pale yellow, the stone can range as far as reddish or brownish in colour, something which can also be influenced by the processing methods used.

Brazil, Madagascar, Argentina, Myanmar, Namibia, Russia and Spain

7

November

Taurus, Leo, Virgo

Legend has it that the citrine was worn by Caesar’s legions as a “breast stone” and a life-saver in battle. This is also the basis for its designation as a “life stone”.

Some citrine pieces

-

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlistCufflinks “Zeppeline” amethyst, peridot, citrine

3.140$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet amethyst, citrine, smoky quartz

5.047$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Coral

The genesis of the red marine plants was surrounded by myths and legends for many years. In his poem Metamorphoses, Ovid depicts the birth of corals out of the narrative of Medusa after she has been defeated by Perseus, and the blood from her head, now bereft of life, is transformed into glowing red coral “branches”. There’s little doubt that the question of whether coral is now a living thing, plant or mineral, has only added to our fascination with the mesmerising undersea plant since ancient times. Apparently alive when under water, but as hard as stone on land – this inconsistency in coral’s nature has always stimulated human imagination, allowing the belief to take root that the substance must be imbued with some kind of magical, healing powers. A sought-after collectors’ item oscillating between the products of nature and human creations in early modern art chambers, the small red branches were painstakingly processed by goldsmiths until they were unique works of art. Coral jewellery has a long tradition to draw upon, therefore.

The colour spectrum of red corals ranges from a delicate pink to salmon-coloured, through light red and medium red, to a dark “ox-blood” red. Coral is by no means just about red, however; the stone can also be found in colours such as white, blue and black, and is extraordinarily eye-catching.

Mediterranean, Red Sea, Canary Islands, Malay Archipelago, Japan and Hawaii

3-4

Taurus 21 April – 21. May

Cancer 22 June – 23 July

Libra 24 September – 23 October

The traditional association of red coral with Medusa’s blood led observers to conclude that this “stone” must have some sort of effect on our lifeblood, and consequently human health. As if this were not enough, it has also been associated over the years not just with the blood of the Gorgons, but also with the blood of Christ, as a result of which it was said to have curative powers and the ability to repel all evil. Paracelsus described the effects of coral as being to ward off detrimental thoughts, nightmares, apparitions and melancholy. It was said to drive out both the evil eye and the Devil, which has led to the long tradition of wearing coral-studded amulets – as often seen on Baroque paintings of infants, for example.

Some coral pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Diopside

green-yellow, blue

Finland, India, Madagascar, Myanmar, Austria, Sri Lanka and USA

5 – 6

Virgo

The Ancients believed diopside was the magical remains of a star which had fallen from Heaven to Earth, and that it supported processes of letting-go.

Some diopside pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistOhrstecker Diopsid, Rhodolith, Saphir, Tsavorit

1.053$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings moldavite, tsavourite, mandarine-garnet

3.941$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEar studs lapis lazuli, tsavorite, diopside

3.899$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Garnet

Garnets have been prized jewellery stones since antiquity. According to ancient myths of sacred garnets, the stones were said to have the power to glow spontaneously from deep within themselves. Not least because of this, they were designated as “Karfunkel” – carbuncle – in the Middle Ages.

What is indisputable, however, is that garnets are distinctive due to their beautiful refraction of light, and their brilliance. The stones can be found in several different colours, some of which are particularly rare, and highly valuable as a result. The most valuable variety of garnet is the delicate to mid-green demantoid, whose name is derived from its diamond-like lustre, and not without good reason. The group also includes the dark-green garnet found in Kenya and Tanzania as tsavorite. This stone is captivating thanks to its extraordinary and intensive green tone. The reddish-violet variety of almandine garnet, whose colouring comes from aluminium and iron, is also highly-prized, and by far the best-known face of garnet. Grossular, rhodolite and hessonite are also part of the garnet family.

Garnet deposits are frequently to be found in magma rocks, or – as in Austria – in rocks such as gneiss or mica slate, which have evolved under high pressure and at high temperatures.

USA, Germany, India, Madagascar, Norway, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Australia, Nepal, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Brazil

6,5-7,5

January

Aries 21 March – 19 April

Leo 24 August – 23 September

Scorpio 24 October – 22 November

Garnet is highly-prized and sacred in Indian culture and in Buddhism; in India, it is considered “the fire of perpetual transformation”. Even Hildegard of Bingen used garnets, based on the belief that they were said to have a healing effect, of strengthening the heart.

Some garnet pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistRingsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistRingsAdd to wishlistRing Citrine, Garnet, Rhodolite, Sapphire

3.014$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Grandln

The German-language expression “Grandln” is used to describe the use of the canine teeth of wild animals, usually those of stags, in jewellery. Hunting trophies have been worn as jewellery since time immemorial. At our workshop, we are also happy to process the Grandln of our hunting customers, continuing the age-old tradition of hunting jewellery – interpreted in a contemporary way, in accordance with our company philosophy. Customers’ wishes in this field are as individual as the customers themselves, and we look forward to helping you realise your projects at any time.

Some Grandl pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Heliotrope

The name of this dark-green stone, whose red speckles result from iron oxide depositions, translates from the Greek term for “solstice”. According to ancient mythology, it was believed that heliotrope created a connection between human beings and the world of the gods, as it was associated with the sun. The long tradition of producing signet rings with armorial engravings using heliotrope endures to this day. When doing this, the coat of arms in question is either created in classic, back-to-front style, to be used as a seal, or cut into the stone in show view.

India, Australia, Brazil, China and USA

Quartz

6,5-7

Aries, Virgo, Libra

Heliotrope played an important role in ancient astrology, and was believed to assist with powers of self-healing and afford courage in decision-making.

Some heliotrope pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Iolite

Scandinavian legends tell of how this violet-blue stone was used by Nordic seafarers to navigate on cloudy days. The sailors were said to have used thin slices of iolite as the first traditional polarisation filter, in what became known as the “Viking Compass”. Since proven by experimental archaeology, the principle is the equivalent of that used in the twilight compass, which continues to be used in aviation at higher latitudes. With this device, polarised light in the atmosphere can help localise the sun when it is concealed behind the clouds. Although its colour is sometimes reminiscent even of sapphire, beautiful clear qualities are extremely rare.

Brazil, India, Madagascar, Myanmar, Norway, Sri Lanka and USA

7-7,5

The properties of iolite described above make it easy to understand why, in Nordic legend, iolite amulets were said to have the capacity to lead lost sailors to the sun, and consequently safely home. To this day, it is viewed as a stone of clear vision, and to counter fears and stress.

Some iolite pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Jade

Jade is one of the oldest cult stones, and plays a key role in almost all the world’s great cultures. Due to its extraordinary toughness, the material was used for weapons and devices in prehistoric times. The first objets d’art to be crafted out of jade were already being produced during the Palaeolithic Age. Thanks to its rich deposits of the stone, a veritable jade culture evolved in China, and the artistry, ethics, philosophy and mythology surrounding jade reached its highpoint. To this day, people in China believe in its healing powers and revere it as a bringer of good luck.

Because jade is one of the world’s toughest materials, it can only be cut using diamond-tipped tools. The flattering shine that makes jade so unique is only produced by careful polishing. The stone’s natural colour spectrum ranges from white, a delicate yellow and lavender violet, through to green, brown, grey and black. The most popular – and expensive – colour variety is what is known as “imperial jade”, whose vibrant emerald green tones make it comparable with gold in value. In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, jade was even more highly-prized than the valuable precious metal gold itself.

Myanmar, China, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico and Russia

6,5-7

October

Ancient Chinese tradition has it that jade symbolises the five essential virtues of wisdom, righteousness, humility, compassion and courage. Jade is said to bring longevity – even immortality if you are very lucky – and stands for the feminine, beauty and nature in Chinese culture. Jade is also revered as a magical stone in other cultures, however. It is often used as a burial gift, for example, or worn as protection from evil spirits. Even in Mesoamerican culture, jade reached a very special position, being used as a stone to heal the kidneys, in sacrifices and as a tribute to the Gods.

Some jade pieces

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistPendant and necklace jade, fire opal, diamonds

18.800$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Jasper

Jasper was already being used to produce tools in prehistoric times. Highly prized by both the Ancient Greeks and Romans, it is also mentioned in the Bible, when it is described as one of the twelve stones to adorn Jerusalem’s city walls in the Book of Revelations. It also makes an appearance in the Song of the Nibelungs, worked into the hilt of Siegfried’s sword. Thanks to its diverse colour spectrum, numerous other stones have been – falsely – attributed to jasper, and traded in its name, over the centuries. It is very rare for the stone to occur in a single colour; it is usually dotted, mottled or striped, and multicoloured. A number of astonishingly large stones have been processed over the years. One of the best examples is the Kolyvan Vase, displayed at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg: this stone is five metres by three metres in size, and weighs around 19 tonnes. In the jewellery sector, jasper is mainly used for cufflinks nowadays, as well as there is a long tradition of processing it for signet rings.

Egypt, Australia, Brazil, India, Canada, Kazakhstan and UruguayM

6,5-7

March

Aries

Jaspers is said to encourage steadfastness and willpower in the wearer, and to lend inner calm.

Kunzite

pink-violet, mauve

Brazil, Afghanistan, Madagascar, Myanmar, Pakistan and USA

Spodumene

6,5-7

February

Libra, Pisces

Some kunzite pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings kunzite, tourmaline, diamonds

16.650$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Kyanite

blue, blue-green, brown

Brazil, Kenya, Myanmar, Austria, Switzerland, Zimbabwe and USA

Kyanite

4 – 4.5 (lengthwise), 6 – 7 (crosswise)

March

Aries

Kyanite is said to help the wearer leave old patterns behind, and to foster decisive, effective action

Some kyanite pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Labradorite

This charmingly iridescent stone was named after its original discovery site, Canada’s Labrador Peninsula, where it was first found in 1770. The stone’s metallic lustre makes a highly lively impression, due primarily to the flashing blue-green colour effects it produces with movement. This not only lends the stone a highly modern appearance, but also makes it beautifully timeless. Thanks to its neutral colouring and subtle shimmer, Labradorite is often highly valued in the field of everyday jewellery. Despite its high adaptability – comparable to its relativeMoonstone – this stone has an unmistakeable character, lending it a very special radiance.

Canada and Madagascar

6-6,5

Aquarius, Cancer

Labradorite is said to foster intuition on the one hand, while strengthening the sense of reality on the other. It is also said to inspire creativity and fantasy.

Some labradorite pieces

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace spinel, labradorite, moonstone

4.320$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace labradorite, peridot, aquamarine

3.530$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet, labradorite, topaz and rubies

2.792$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Lapis Lazuli

Michelangelo created his famed fresco at the Sistine Chapel with it, Cleopatra used it for her beguiling eye shadow, and Napoleon liked to carry it in his trouser pocket as a protective lucky charm. Highly diverse, lapis lazuli was also viewed as a protective stone by the Greeks, Romans and Indians, and ascribed divine power and magical properties. Archaeological finds of burial offerings, historical pieces of jewellery and cult objects bear witness to the stone’s high esteem and religious significance within past high cultures, including the Sumerians, Akkadians and Babylonians. The stone is mentioned in the latter’s Gilgamesh Epic, dating back to at least 1,800 BC. The Egyptians used lapis lazuli for their seal rolls, just as our company still uses it in the traditional manner to produce the seal stone in signet rings.

The finest qualities of the stone, whose chromophoric substance is sulphur, boast uninterrupted colour distribution. Fine pyrite interspersions are a sign of its authenticity. When wearing lapis directly next to the skin, it is important to remember that the surface, although waxed frequently for its own protection, remains highly sensitive to environmental influences and should be protected against any kinds of acids or brines, perfume, detergent, oils and creams, insect repellent and hairspray, as well as perspiration, as these can all damage the colouring of the stone and cause blemishing.

Afghanistan, Russia, Chile, Angola, Canada, Pakistan and USA

5-6

September

Sagittarius, Virgo, Libra

In a similar way to the codes of the charmingly celebrated symbolism of fans, royal courts in the 18th century used a symbolic language of stones, embodying the themes of love and happiness. Rings featuring labyrinthine initials on lapis lazuli were considered appropriately chivalrous gifts.

Lapis has been designated a heaven stone since time immemorial, and numerous positive properties ascribed to it. Even today, lapis lazuli is said to strengthen self-confidence, have a positive effect in the solving of conflicts, and to increase optimism in the wearer.

Some Lapis lazuli pieces

-

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet aquamarine, jade, lapis, peridot, rock crystal, topaz

3.266$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistBroochesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBroochesAdd to wishlistBoris Podrecca “Basilea” brooch coral, pyrite, pearl

7.166$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBraceletsAdd to wishlistBracelet amethyst, tourmaline, citrine

6.312$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEar studs lapis lazuli, tsavorite, diopside

3.899$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Malachite

Malachite’s use as an expensive pigment within oil painting, in cosmetics and in magnificent works of art – in addition to its function in jewellery – are all ample evidence of the stone’s diversity and unique colour quality. Examples of important artefacts in which it has been used include the death mask of Tutankhamen, which is set with malachite, lapis lazuli and turquoise, Raphael’s famous Sistine Madonna, and the impressive, once-painted Terracotta Army of Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huang, which continue to contain evidence of the remains of colour pigments. Although the malachite pigments used in painting have a stable constitution – unlike the pigment azurite, which turns green under the influence of moisture – malachite, too, can fade if exposed to direct sunlight for long periods, and lose its shine if brought into protracted contact with water.

Malachite has also enjoyed huge popularity in the field of craftsmanship. When visiting the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, you can admire the so-called Malachite Room, home not just to monumental malachite columns, but also to a chimney and table clad entirely in the stone. At one time, entire wings of pianos were being produced in Russia with opulent gold-trimmed malachite cladding. The vast deposits of the stone in the Urals region once used to do this are now nearly exhausted, however.

Russia, Australia, Germany, Congo, Morocco, Austria and USA

3,5-4

Aquarius, Capricorn

Historically worn in amulets to counter danger and disease, today the stone is said to have positive effects on self-awareness and levels of satisfaction. Once dedicated to the Goddess Hathor in Egypt, European antiquity saw the Greeks attribute the stone to Aphrodite, and the Romans to Venus, which undoubtedly dates back to its association with the themes of beauty, sensuality, seduction and hope.

Some malachite pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistPendant and necklace malachite, coral

2.455$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistBroochesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistBroochesAdd to wishlistBoris Podrecca “Basilea” brooch coral, pyrite, pearl

7.166$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Moldavite

Created by a meteorite impact within the borders of what is now the Czech Republic – with a number of smaller strewnfields in neighbouring countries – this stone was first discovered in the 18th century. Moldavite is not a mineral, but a natural glass. Although the stone was very popular for a while during the art nouveau era thanks to its beautiful bottle-green colouring, its admirers lost confidence due to the accumulation of forgeries using plain bottle glass. It returned to the spotlight briefly when Queen Elizabeth II received a gift from Switzerland of a tiara decorated with moldavite to mark her tenth jubilee in 1963.

bottle-green to brown-green

Czech Republic, Austria and Germany

5,5

Moonstone

Moonstone owes its poetic name to the fact that its shimmering is said to be reminiscent of gentle nocturnal moonlight. This so-called “moonstone effect” can actually be traced back to a phenomenon known as adularescence: while refraction and reflection of the light on the specific crystal structure cause the stone to appear dull, the overlapping of the reflected rays of light eventually creates the much sought-after lustre.

Depending on the stone’s site of origin, its seductive, velvety and highly subtle colour change can vary in its fundamental tone, ranging from white and sandy colours, through grey and brown, to orange. Moonstone’s timeless character, and the flexibility associated with its muted colourfulness, make it a very popular everyday companion with that certain, highly contemporary, extra something.

Sri Lanka, Australia, Brazil, India, Madagascar, Austria and USA

6-6,5

June

Cancer, Pisces

Moonstone is said to strengthen and foster personal intuition, convey inner peace, conquer stress and fears, and support femininity.

Some moonstone pieces

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace spinel, labradorite, moonstone

4.320$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings tsavorite, rock crystal, moonstone

4.299$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Mother of pearl

The exquisite inner workings of certain saltwater and pearl oysters – “mothers-of-pearl”, so to speak – have fascinated humans for centuries. Their iridescent shimmer doesn’t just adorn jewellery beautifully; it has also been used at European royal courts, in magnificent inlay work on works of art and the contents of treasure chambers. Mother-of-pearl’s visible shimmer when moving is caused by light interference from the different fractions of the colour spectrum. At our workshop, we use mother-of-pearl to produce both trimmings for dress coats and cufflinks to order, as well as in the background material for expensive rock crystal miniatures

white to grey, shimmering blue-green

Inland waters and in almost all warm seas (except western Atlantic)

Calcium carbonate compound

2,5-4,5

June

Cancer, Capricorn

Mother-of-pearl is said to help relieve allergies and to disperse psychological tensions, increasing inner happiness

Some mother-of-pearl pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Onyx

Repeatedly described as a “stone of the night”, the opaque appearance of onyx only makes its aura more mysterious still. In the Art deco period in particular, the stone was prized for its extravagance. Its black colour – a hark back to its volcanic origins – blended in perfectly with the discreet use of colour scheme at the time, and worked beautifully in combination with diamonds in particular. The contrasts between the two stones emphasised the unmistakeable qualities of the other – surely the objective of any truly timeless partnership. The impermeable unity of the onyx underlines the steely lustre of the diamond; at the same time, the glassily clear appearance of the diamond lends even more expressive power to the discreet elegance of onyx. “Never change a winning team”, as the trainer who helped England win the World Cup once said. How right he was. And with this in mind, we are always happy to use this unbeatable duo, in cufflinks and dress coat trimmings first and foremost. The subtle understatement they provide enables even the most discreet of gentlemen to strike a truly impressive figure, no matter what the social occasion.

Brazil, India, Mexico, Yemen, USA, Uruguay and Pakistan

6,5-7

February

Capricorn, Leo, Scorpio

The sought-after healing presence of onyx is said to have a positive effect on the wearer’s inner stability and powers of resistance. It is considered a stone of strength in general, and said to keep evil at bay. Historically, it has also been used to produce mourning jewellery.

Some onyx pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Opal

The Ancient Greeks believed opal was created from the tears of joy shed by Zeus, Father of the Gods, when he eventually won out in his battle against the Titans. Counter to its unhappy reputation, Queen Victoria chose the opal to be her favourite stone. By giving all her grandchildren generous gifts of the stones, the Empress of India dispelled their reputation for bringing bad luck, as nothing dramatic happened to the children. So why not copy her and indulge yourself in this stone’s deliciously colourful iridescence?

The opals group also includes both the shimmering, rainbow-like “noble opals” and orangey-red “fire opals”, which don’t exhibit this opalescent effect. Fire opals usually tend to be opaque, and only rarely clear. If they are, then you can be more or less certain you’re dealing with a rarity, and something genuinely valuable.

The noble opals, on the other hand, include the white opal, the rarer so-called “black opal” (whose primary colour actually ranges from dark grey through to dark blue and dark green), and the particularly valuable boulder and harlequin opals. Although boulder opals are also dark, they also offer a more intense play of colour and greater strength. The transparent to translucent harlequin opal, with its impactful, segmented colour patterns, is amongst the most sought-after opals in the world today.

Since between 3% and 30% of opals actually consists of water, it’s important that the stones be kept sufficiently moist at all times, to prevent moisture loss and material damage in the form of fissures or a loss of lustre. Storing opals in damp cotton wool, for instance, preserves their colour play and prevents them from ageing. Under no circumstances should opals be stored in an environment with low levels of humidity for extended periods – in safes, for example – as this can irreversibly damage the stone. You should also be cautious when applying pressure or bringing the stone into contact with cosmetics, soap or other cleansing agents.

Today, Australia and Ethiopia; historically, best qualities from Slovakia

5,5-6,5

October

The opal has long been considered the stone of providence and prophecy, while the Ancient Greeks believed it gave the wearer the gift of insight into the constitution of things.

Some opal pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Paraiba tourmaline

This noblest of all the varieties of tourmaline takes its name from the eponymous Brazilian state of Paraiba, in the north-east of the country, where it was first discovered in the 1980s. Paraiba tourmalines originating in Brazil remain the most sought-after and expensive qualities of the stone to this day, despite the fact that the mines are now largely exhausted. The stones have since come to be viewed as wearable investments, as prices, particularly for the highest qualities, have risen continuously in recent years. No other coloured precious stone has experienced quite such a rapid increase in value as the Paraiba tourmaline in the past 30 years. The main reason for this is undoubtedly its rarity and unusual “neon-like” colouring, the result of copper and manganese in the stone. Depending on the stone’s origin, this colouring varies from blue, through neon-blue and blue-green turquoise tones, to luminous green. The jewellery trade does its best to live up to this unusual appearance by using descriptions of its colouring such as “neon”, “electric”, “vivid” and “glowing”. Further deposits occur in Mozambique and in Nigeria, where the majority of Paraiba tourmalines traded today come from.

Brazil, Mozambique and Nigeria

Tourmaline

7-7,5

October

Libra, Capricorn

Some paraiba tourmaline pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEngagement ringsAdd to wishlist

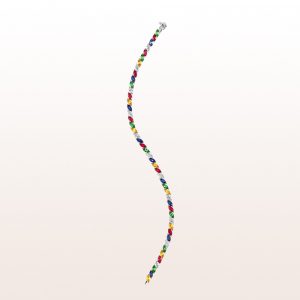

Add to wishlistEngagement ringsAdd to wishlistRing paraiba-tourmaline, diamonds

7.482$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEngagement ringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEngagement ringsAdd to wishlistRing paraiba-tourmaline, diamonds

19.759$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings diamonds, aquamarine, paraiba-tourmaline

16.967$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Pearl

The legendary aura of pearls dates back to an era before the stones were cultured artificially. Before pearls began to be cultured commercially in Japan at the beginning of the 20th century, pearl divers along the warm coasts off India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the Arabian Peninsula had had to open countless closed mussels – an incredible physical effort – to find naturally-grown pearls, known as “Oriental pearls”, purely by chance. Today, Oriental pearls found in this way would be almost priceless. Appropriately costly, often even more expensive than most precious stones, these natural pearls had enormous symbolic character.

Tradition has it that Indian and Chinese rulers laid their feet on sumptuous carpets of pearls – an idea later taken up by the Maharajah of Baroda when he commissioned a lavish carpet of pearls in 2009, later auctioned for USD 5 million. Eventually pearls also made it to Egypt, Greece, Rome and Byzantium, either on trading routes or as the booty of war, where they were considered impressive status symbols. Emperor Caligula scored points with his pearl-inlaid slippers, for instance, while the ladies of Rome liked to have the interiors of their carriages lined with the stones.

Mentioned in the Book of Revelations, pearls acquired an increasingly religious character from the Middle Ages onwards, as they began to be viewed as an allegory for the love of God. This mindset inspired the Spanish Conquistadors of the 16th century to process the pearl treasures captured from the temples of the Aztecs into artful beneficences back in Europe. Examples include the Cloak of the Madonna in Toledo Cathedral, which is inlaid with 80,000 pearls. Even secular noblewomen such as Maria de Medici, wife of Henry IV of France, liked to dress in lavish, pearl-encrusted robes, however. Legend has it that she owned a dress decorated with over 3,000 diamonds and 32,000 pearls. Due to the incredible weight of the dress, however, she could hardly walk when wearing it, prompting derision amongst her critics at the French court. The greatest such extravagance to be recorded in modern times was in 1908, when the last Empress of China was buried together with a sumptuous pearl blanket. Regrettably, this was later plundered in the throes of the country’s revolution.

There are a range of decisive criteria for evaluating the quality of pearls, as well as the question of whether they are freshwater, cultured saltwater or even the immeasurably expensive, natural Oriental versions of the stones. These criteria include the stones’ lustre, also referred to as their enamel, the quality of their surface, their size, form, colour, and the thickness of the mother-of-pearl. Freshwater pearls have a weaker lustre, and are rarely round. In the case of cultured saltwater pearls, a distinction is drawn between Akoya, Tahitian and South Sea pearls, depending on their origin. Originally from Japan, Akoya pearls are now also cultured in China and Vietnam, and feature the thinnest layer of mother-of-pearl out of the three types of cultured pearl. Tahitian pearls, made famous in Europe by Kaiserin Eugenie above all, are captivating thanks to their dark colouring, which ranges from grey, silver or black, through blue-green, to the nuanced green-pink colour known as “peacock”. The white, silver-tinted and gold-yellow South Sea pearls, which occur in Indonesia, Australia and the Philippines, are the most opulent of all cultured pearls, reaching an impressive size of up to 20 mm.

Natural pearls (also known as Oriental pearls), cultured pearls, salt- or freshwater

Calcium carbonate compound

2,5-4,5

June

Cancer, Capricorn

In ancient Chinese poetry, the pearl has always been a symbol of wealth and dignity, viewed as a symbol of a long and happy life. For many centuries it was deemed the epitome of perfection and beauty. In a mystical sense, pearls are said to show their wearer the way to confront problems and to strengthen intuition. In Chinese medicine, the aminoacids and trace elements contained in pearls are said to have a calming and detoxifying effect, as well as helping to regenerate cells. Pearls also played an important role in western medicine and pharmaceutical teaching until the 19th century.

Some pearl pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings quartz, sweet water pearls, diamonds

2.144$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Peridot

The question of whether there is life out in space can be answered as follows: there’s certainly peridot! This is because in Russia, cut peridots are famous for having originated from a meteorite that fell to Earth in eastern Siberia in 1749. Down here on Earth, historic excavation sites include the area surrounding the Red Sea, from where the Crusaders brought the peridot back to Central Europe. Used a great deal for religious purposes in the Middle Ages, this stone emerged as the favourite stone of the Baroque era, and its warm, fresh mid-green tones mean it continues to captivate wearers to this day.

Myanmar, Australia, Brazil, China, Eritrea, Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan and South Africa

6,5-7

August

Libra

In the past, peridot was said to have healing and magical powers, to offer protection from nightmares and to give its wearer the gifts of power and influence.

Some peridot pieces

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace turquoise, apatite, peridot, zircon

1.738$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Precious woods

As interest in new materials increased during the Art deco era, people also began working with precious woods. This pleasure at how such woods can be used is based primarily on the charming contrasts the materials offer with precious stones, an effect which endures to this day. As well as ebony, the precious woods processed at our workshop include rosewood and amboina, or Andaman redwood, as well as the wood of the curly maple, which shifts in colour between green and black.

black, red-brown, greenish-black and dark brown

Ebony, Amboina wood, Rosewood, Flamed maple

Some precious woods

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Prehnite

yellowish-green, brownish-yellow

Australia, China, Scotland, South Africa and USA

6-6,5

Some prehnite pieces

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace smoky quartz, lemon citrine, prehnite

7.376$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace prehnite, dipside, tourmaline

1.633$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Quartz

As well as rock crystal, citrine, rose quartz, amethyst, blue quartz and smoky quartz, the group of macrocrystalline quartzes includes eagle eye, cat’s eye and tiger’s eye.

The name “crystal” is derived from the Greek word for “ice”, since in ancient times, it was believed that rock crystal was “eternally frozen” – ice transformed into stone, in other words. Here’s an amusing anecdote from Roman times: since rock crystal remains cold for quite some time even at warm temperatures, some wealthy Romans often kept it in their homes so they could use it to keep their hands cool in the summer months. Later often used for ostentatious drinking vessels and works of art, rock crystal continues to enjoy huge popularity to this day. The stone is frequently used in our custom-made production of miniature paintings, for example.

Unlike rock crystal, rose quartz is usually opaque, and has titanium and manganese to thank for its pink colouring. Sites where the stone is excavated can be found in countries including India, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia and Sri Lanka.

The brown colouring of smoky quartz, on the other hand, originates from natural or artificial gamma radiation, and frequently also features inclusions of rutile needles. The stone is found, amongst other places, in Russia and Scotland.

Brazil, Madagascar, USA and Alpine region

Group of macrocrystalline quartzes

7

January – Rose quartz

April – Crystal quartz

Rock crystal Gemini, Capricorn and Leo

Rose quartz Taurus and Libra

Smoky quartz Capricorn

The Romans viewed rock crystal as the “seat of the Gods”, which was said to lend its wearer wisdom, courage and loyalty in love.

Some quartz pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistPendantsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistPendantsAdd to wishlistPendant amethyst, diamond, quartz, tsavorite, tourmaline

7.071$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings rose quartz, amethyst, diamonds

1.528$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Rhodochrosite

Already highly prized at the time of the Incas, rhodochrosite is also known as the “Rose of the Incas” to this day, and is Argentina’s national stone. Discoveries of burial objects have revealed the stone was already well-known in Ancient Egypt too, where it was mined, together with manganese, in the Sinai Peninsula. While its resounding German-language name Himbeerspat, or “raspberry spar”, refers to its pink to red colouring, the stone also occurs in white, yellow and brown. It frequently appears with white banding, the result of its deposition taking place in layers under the influence of water. This layered structure also explains rhodochrosite’s low levels of hardness and resistance to heat.

Argentina, Germany, Romania, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, Gabon, Russia and Japan

Rhodochrosite

3,5-4,5

Taurus, Cancer

Rhodochrosite is said to lend its wearer vitality and happiness, and is viewed as a protective stone in the Indian tradition. According to an Inca legend, its creation arises out of forbidden love: after a warrior of the indigenous people is said to have fallen in love with a virgin dedicated to the sun god, he was transformed into a stone the colour of a red rose as punishment. In Argentina, legend has it that rhodochrosite brings unconditional love, happiness and forgiveness.

Some rhodochrosite pieces

-

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistStud earrings citrine, peridot, rhodolite, sapphire

1.159$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings rhodochrosite, crystal quartz, zircon

3.425$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings carnelian, rhodochrosite, topaz

3.730$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Spinel

Spinel – the long-misunderstood genius. Until around 150 years ago, when they were recognised as an independent material, these stones were still being (wrongly) classified as rubies, probably as a result of their excavation sites being partly located in ruby mines. The fact that several cape stones in the English and Bavarian crown jewels once dubbed as rubies are actually spinels shows the stone’s potential for flights of fancy.

Like tourmalines and sapphire, spinels can be found in a wide variety of colour tones, with good red qualities the most valuable and very interesting in terms of price trends.

Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Australia, Brazil, Madagascar, Nepal and Thailand

8

Aries

Some spinel pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace spinel, labradorite, moonstone

4.320$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Tanzanite

Tanzanite is a relatively “young” stone, not actually having been discovered until 1967. Despite this, it has already experienced a meteoric rise by any standards. The stone’s name is derived from the only place it has been found to date, in Tanzania. The conditions under which tanzanite deposits were created, at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, are considered so unique that geologists estimate the probability of further deposits of the stone being found at approximately one in a million.

Tanzanite sparkles in an electric violet blue, lively ultramarine, deep royal blue and a rich indigo. The best qualities are more than enough to place its appearance on a level with the sapphire. The stones usually feature a clear violet tone, which intensifies under artificial light. Most deposits of tanzanite are originally brown at the time of their discovery, and only start to take on their more familiar blue appearance with heating.

Since tanzanite is a relatively brittle stone, it is extremely important to protect the stone from knocks, pressure and large variations in temperature, and it should not be cleaned in ultrasonic purifiers.

6,5-7

December

In 1967, after lightning strikes had set the surrounding hills alight, Masai herders noticed the brown crystals were turning blue in colour. Since then, a popular belief has gained ground in Tanzania that the precious stone has unique spiritual properties, and that it promotes spiritual growth. It is also said to have calming and emollient properties.

Some tanzanite pieces

-

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistCufflinksAdd to wishlistCufflinks “Zeppeline” tanzanite, rubellite

5.480$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistEarringsAdd to wishlistEarrings rose quartz, diamonds, tansanite

4.204$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistNecklacesAdd to wishlistNecklace garnet, tanzanite, rubellite

3.056$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Tiger's eye

gold-yellow, gold-brown

South Africa, Australia, China, India, Namibia, Ukraine and USA

Quartz

6,5-7

November

Virg, Leo, Gemini

Tiger’s eye confers courage and certainty, and has a positive effect on the bronchial tubes.

Some tiger's eye pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Topaz

Topaz is already being mentioned by Pliny the Elder, and in the Old Testament. The Bible describes it as one of the stones to be mounted in the golden medallion of a high priest, and as one of the twelve foundation stones in the wall of the new Jerusalem. Highly prized over centuries, extraordinarily large and beautiful examples of topaz could be found in the crown jewels and rulers’ crowns of a variety of royal courts.

Like other coloured stones, topaz features a diverse colour spectrum. This ranges from the most frequent combination, yellow with a light red tint, to red-brown, the (particularly valuable) pink and reddish-orange, red-violet, through to light-green and light-blue, which is also occasionally used as a visual substitute for aquamarine.

Numerous excavation sites are known of worldwide, with the world-famous pink-orange and orange-red stones, known as imperial topazes, only found in Brazil.

8

November

Gold topaz: Gemini and Leo

Blue: Sagittarius and Aquarius

The ancient Greeks were convinced topaz lent its owner strength. Later, during the Renaissance era, it was thought the stone had the power to break an evil spell. In India, meanwhile, it was believed for many centuries that a topaz worn above the heart would bestow long life, beauty and intelligence upon its owner.

Some topaz pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Tourmaline

Although this stone was already known of in the Mediterranean region in antiquity, the Dutch only actually began importing tourmaline, from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to western and central Europe, in 1703. The name of the new precious stones comes from a Sinhalese word meaning “stone with mixed colours”. This is highly appropriate for the colourful varieties that enjoy unbroken popularity to this day, with designations such as verdelith (green), indigolite (blue) and rubellite (pink-red).

Two of the most valuable varieties of the stone are paraiba tourmaline, named after the mines in Brazil where it was first excavated, and rubellite, mentioned above. Both these varieties have seen rapid price increases in recent years. While the incredible colour nuances in paraiba tourmaline can be surprising, moving between light turquoise and electric green, the most sought-after qualities of rubellite will give the ruby a run for its money in value.

7-7,5

March

Rubelite: Aries and Libra

Verdelite: Capricorn

Tourmalines are said to have a reassuring and invigorating psychic effect. The stone encourages our pursuit of harmony and clarity in life; black tourmaline in particular is said to have one of the strongest protective effects against negative energies.

Some trourmaline pieces

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Tsavorite

Like tanzanite and Paraiba tourmaline, tsavorite takes its name from one of its most important discovery sites – the region surrounding Tsavo National Park in Kenya, very close to the Tanzanian border, where it was discovered at the end of the 1960s. In mineral terms, tsavorite is a green garnet, from the group of grossularites. Thanks to its deeper, more intense colouring, tsavorite differs from demantoid, another green garnet, which is significantly lighter and can range from a more yellow tint through to sage-coloured. The most beautiful examples of the stone can compete strongly with the emerald, particularly when it comes to what is known as its “fire”. When it comes to clarity and brilliance, in fact, the stone can even exceed the emerald. Its intense sparkle is the result of its high refractive index, something it has in common with all the stones in the garnet family. The stone’s green colouring, which lends it an extremely lively effect, is produced by the chrome and vanadium it contains. Essentially, this is a highly rare stone, with examples larger than 3 ct in size exceptionally uncommon and expensive.

Kenia and Tanaznia

6,5 – 7

May

Some tsavorite pieces

-

Add to wishlistRingsAdd to wishlist

Add to wishlistRingsAdd to wishlistEva Petrič “Chromosomes in love” ring tsavorite

1.686$ incl. 20% taxAdd to wishlistAdd to wishlist -

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

-

Add to wishlistAdd to wishlist

Turquoise

Turquoise is one of the oldest jewellery stones in human history. It was already being mined in prehistoric Mexico, and was considered a holy stone by the Aztecs, frequently being used as a burial object. A similar tradition developed in ancient Egypt from 5,000 B.C. onwards, where turquoise was used to fashion magnificent jewellery and marquetry. One of the most famous examples is undoubtedly the death mask of Tutankhamun, which is laid out with turquoise.

In ancient Israel, too, turquoise was found in the copper mines of King Solomon; legend has it that the first mine was opened by Abraham’s son Isaac around 2,100 B.C.. In ancient Persia, a key excavation site of the stone, a law was in place stating that the best turquoises could not be traded, and were the property of the Shah. And in Tibet, where the stone was viewed as sacred, it was considered more valuable than gold, and for a time even used as a method of payment.